A recent paper by Dr. Darshan Singh et al titled “Severity of Pain and Sleep Problems during Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth) Cessation among Regular Kratom Users” suggests that kratom may have less burdensome withdrawal symptoms than methadone. Given these findings, and methadone’s current place as the world’s substitution treatment drug of choice, this article will:

- Define substitution treatment and, more broadly, harm reduction

- Describe Portugal’s exemplary case study in harm reduction

- Home in on substitution treatment, one of the pillars of harm reduction

- Look at Dr. Singh’s aforementioned work

- Conclude with a discussion about possible futures for kratom and methadone within the context of harm reduction and substitution treatment

This article will be taking up some of the arguments laid out in our Beginner’s Guide to Kratom. If you’re visiting Kratom Science for a more comprehensive look at kratom strains, kratom dosages, and kratom effects, we recommend you start there.

What is Harm Reduction?

Harm Reduction International defines harm reduction as follows:

“Harm reduction refers to policies, programmes and practices that aim to minimise negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws.”

In other words, harm reduction sets realistic expectations for those suffering from a physical addiction by providing those individuals with care, counseling, and the resources to change their situation.

Harm reduction is about treating a disease called addiction.

The Case of Portugal

In 2001, with fully 1 percent of its population addicted to heroin, Portugal radically changed how it thought about drug treatment: it decriminalized drug use.

From then on, Portuguese citizens caught with less than a ten-day supply of any drug have received a citation akin to a parking ticket and have been directed to mandatory counseling sessions from a “Dissuasion Commission.”

These commissions are composed of a group of social workers who are trained to nonjudgmentally educate Portuguese citizens about the dangers of becoming drug dependent. They’re the core of Portugal’s approach to harm reduction.

But Portugal goes even further, providing heroin users with clean hypodermic needles, thereby drastically reducing the probability that heroin users will contract HIV. Portugal provides heroin users with more intensive physical and psychotherapy counseling.

And Portugal weans heroin users during detoxification with Methadone Maintenance Therapy (MMT).

Almost twenty years later, João Castel-Branco Goulão, the public health expert credited with architecting Portugal’s drug policy reformation, has been called a “national hero” by former prime minister António Guterres. Some facts supporting Guterres’s moniker for Goulão:

- Only .25 percent of Portuguese people currently use heroin. (A 75 percent drop in heroin use since Goulão’s reforms were put in place.)

- Portugal’s drug-related mortality rate is currently the lowest in Western Europe, “one-tenth the rate of Britain or Denmark.”

- HIV infection rates in Portugal have dropped from 104.2 new cases per million in 2000 to 4.2 cases per million in 2015.

Portugal’s success creating a healthful culture for its citizens cannot be understated. It has used harm reduction strategies to improve the quality of life of its people.

Substitution Treatment, Methadone, and Kratom

Substitution treatment, or the controlled prescription of other opioids to help ease the tremendous pain of the heroin addict’s withdrawal, is one of the most powerful of Portugal’s (and the world’s) harm reduction strategies. Methadone is the drug most often prescribed as a substitution for heroin—so much so that Methadone Maintenance Treatment has come to be recognized as a metonym for substitution therapy itself.

Why is substitution treatment necessary?

The withdrawal symptoms associated with heroin use are notoriously extreme. They have been depicted in television and movies, Requiem for a Dream being perhaps the most affecting—and sensational. Still, heroin withdrawal can be fatal, so that depiction is not totally unfounded. Heroin withdrawal symptoms almost always include anxiety, agitation, nausea, sweating, and a seemingly endless list of other adverse conditions.

Methadone, which is, like heroin, a synthetic opioid, alleviates most of these conditions.

However, methadone does not cause “the high” heroin users crave.

Accepted thinking therefore suggests that methadone allows recovering addicts to wean themselves from heroin’s proverbial carrot (the high) without also being forced to endure heroin’s stick (the incredible withdrawal symptoms).

So what’s the problem with MMT?

To continue the metaphor, methadone carries a stick of its own. In fact, it carries quite the same stick as heroin; the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction reported in 2017 that methadone-related overdoses exceeded those of heroin-related overdoses in Croatia, Denmark, France, and Ireland. Moreover, methadone’s withdrawal symptoms are almost identical to heroin.

The net result is that MMT patients must undergo a tightly controlled weaning schedule from methadone itself, therefore extending patients’ rehabilitation schedule and perhaps limiting their sense of autonomy.

“Severity of Pain and Sleep Problems during Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth) Cessation among Regular Kratom Users”

Between 2016 and 2017, Dr. Singh administered two surveys to 170 men in Malaysia, where kratom “is used as a folk remedy for its curative properties, and as a substitute for illicit opiates.” These men were each:

- eighteen or older,

- self-reported kratom users,

- had been using kratom for at least two years,

- and had had experience with kratom cessation over the previous six months.

They were moreover excluded from participation in the study if they:

- tested positive for any other opioid,

- were currently in a drug rehabilitation program,

- or had a previous history of chronic pain and/or sleep problems.

The surveys administered to the men were the Brief Pain Index (BPI) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), both of which have reliable alpha scores.

And the results of the surveys?

In his conclusion, Dr. Singh asserts that “cessation from regular kratom tea/juice use is not associated with prolonged or severe pain or sleep problems, as compared to opioid withdrawal symptoms reported by researchers like Rosenblum et al. (2003), Peles et al. (2006), and Dhingra et al. (2015).”

In all three of the above reports, the opioid in question was methadone.

Moreover, Singh continues,

“Our findings lend support to earlier claims based on self-reports that kratom is less likely to cause detrimental health effects as compared to opioids (Grundmann 2017; Pinney Associates 2016; Prozialeck 2016; Singh, Narayanan, and Vicknasingam 2016; Swogger et al. 2015; Tanguay 2011). Our results indicate that cessation from chronic and regular kratom tea/juice use (with an average of 76 mg to 115 mg of mitragynine dose daily) was associated with moderate pain symptoms and sleep problems.

However, these effects appeared to be relatively mild, since the majority of the participants did not seek treatment for their pain and sleep problems and, in fact, the withdrawal effects only lasted between one and three days. Most regular users in traditional contexts knew how to self-treat their kratom withdrawal symptoms (Assanangkornchai et al. 2007; Saingam et al. 2016).

Notice that Singh does group kratom with other opioids. While kratom’s neurochemical behavior is “opioidic,” its complex mix of alkaloids creates responses in the human body that are distinct from class opioid behavior. For example, as discussed in our Beginner’s Guide to Kratom, kratom does interact with β-arrestin-2, the receptor associated with the respiratory depression that causes overdoses in both heroin and methadone users.

Finally, kratom’s withdrawal effects are not only less severe than those of methadone, Singh reports—kratom users seem to be able to treat them on their own.

Our study suggests that cessation from regular kratom tea/juice consumption was not associated with prolonged and severe pain and sleep problems in regular kratom users in traditional settings in Malaysia. Kratom withdrawal symptoms appear tolerable. Thus, its potential use as a safe substitute for illicit opiates merits serious scientific investigation.

In Conclusion

In no way should this article be read as advocacy for kratom as an ingredient in polydrug cocktails, or even kratom high as a legal high.

And it certainly isn’t a criticism of Portugal’s drug policy reform. Kratom Science supports civil, humane, balanced approaches to drug use. Kratom Science supports harm reduction.

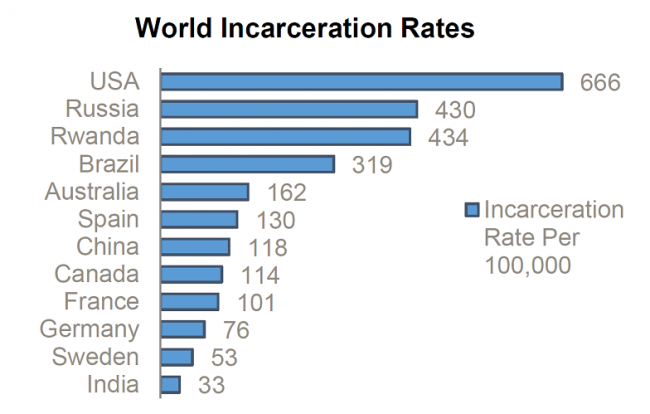

To go further, compare Portugal to the “spectacular failure” of the United States’ War on Drugs, where the Smithsonian estimates that heroin use has risen from .33 percent to 1.61 percent since 2011, where billions have been spent incarcerating addicts, and where, in 2016 alone, 64,000 people died from heroin overdose. For context, as many Americans died in the Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars combined.

However, Portugal’s sensible drug laws should not be confused with the ultimate, conclusive end to all drug reforms policy, either. Good can improve.

Kratom Science agrees with Dr. Singh as well: kratom needs to be taken seriously as a tool for combating opiate withdrawal. Kratom’s psychoactive effects are mild, and his study seems to propose that its withdrawal symptoms are also mild.

This does not suggest, of course, that kratom should immediately replace methadone the world over. Singh’s study has several limitations. No one would deny those.

But also remember that kratom is a member of the Rubiaceae family—the same as coffee. Dr. Singh’s study indicates that Kratom’s withdrawal symptoms are more like its cousin’s than other opioids’.

We therefore need to ask:

- Is it possible that kratom is better at treating opiate withdrawal symptoms than methadone?

- Would giving patients access to a milder substance that they could control increase their sense of self-determination?

- What tests would need to be conducted in order for Portugal, and Europe, to—officially or unofficially—sanction kratom use for treating opiate withdrawal symptoms?

- Why aren’t these tests being conducting?

Sources:

Blakemore, Erin. “U.S. Heroin Use Has Risen Dramatically Since 2001.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 29 Mar. 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/us-heroin-use-rose-dramatically-180962710/.

Brown, Chris. “How Europe’s Heroin Capital Solved Its Overdose Crisis.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 2016, www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/portugal-heroin-decriminalization/.

“European Drug Report 2017: Drug-Related Harms and Responses: Drug-Related Harms and Responses: Opioid-Related Deaths Fuel Overall Increase.” European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2017, www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2017/html/harms-responses/opioid-deaths_en.

Fonseca, Gonçalo. “Want to Win the War on Drugs? Portugal Might Have the Answer.” Time, 1 Aug. 2018, time.com/longform/portugal-drug-use-decriminalization/.

Kristof, Nicholas. “How to Win a War on Drugs.” The New York Times, 22 Sept. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/opinion/sunday/portugal-drug-decriminalization.html.

Singh, Darshan, et al. “Severity of Pain and Sleep Problems during Kratom (Mitragyna Speciosa Korth) Cessation among Regular Kratom Users.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, vol. 50, no. 3, 2018, pp. 266–274.

Pingback: Nine Things Body Builder Anthony Roberts Gets Right (and Wrong) About Kratom Use in Athletics | Kratom Science - Europe

Pingback: Las Nueve Cosas Sobre lo Que el Fisioculturista Anthony Roberts Tiene Razón (y la Una en Que se Equivoca) Sobre el Uso de Kratom en el Atletismo | Kratom Science - Europe

Pingback: Common Sense Policies: Are Portugal and Kratom a perfect pair? | Kratom Science - Europe

Pingback: Portugal y kratom: ¿la pareja perfecta? | Kratom Science - Europe